The Titanic Master-at-Arms who commanded lifeboat 16 is revealed for the first time.

These are the first pictures published of the enigmatic Henry Joseph Bailey, one of two men in the role of ship’s disciplinarian, but the sole survivor of the pair.

With raging controversies over both gunfire on the Titanic and claims that the steerage were restrained, which continue to this day, it is remarkable that Bailey was never called to give evidence.

Tracing the man who might have shed light on much of the evacuation - and particularly events on the port side, aft, where there was evidence of trouble – may sometimes have seemed as elusive as pinning down the truth of the swirling rumours of violence.

Bailey has evaded detection because he did not start life as ‘Henry Joseph Bailey.’ Instead his baptismal name was Job, after the Biblical figure who was persecuted by a series of trials in order to test his faith.

Although christened ‘Job Henry,’ the young Bailey seems to have lost patience with his difficult first name, and to have simply called himself Henry when dealing with officialdom.

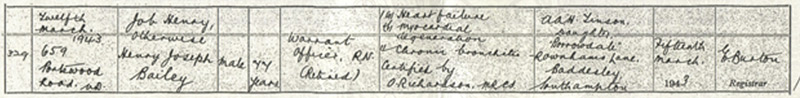

Within his family he was always known as ‘Joe’, perhaps as a form of compromise. As a result, his death cert records the eventual passing of a Job Henry Bailey, also known as Henry Joseph.

Bailey was born on June 22, 1865, the day before the surrender of the last significant Confederate force in the American Civil War, and less than a fortnight before Lewis Carroll published Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland.

With dark brown hair, blue eyes and a ruddy complexion, he grew into a sturdy lad, living with his family in the Highfield district of Southampton.

The first son of labourer Henry Bailey and his wife Charlotte, who already had two girls, the youngster soon had to make his way in the world.

He entered the Royal Navy on October 6, 1880, aged 15, fulfilling the role of “Boy, second class.”

Three years later, on his 18th birthday, he signed for a further ten years. When at length that contract was fulfilled, Bailey was wedded to his sea career and stayed on.

But he was also wooing – he sent this picture of his service vessel, HMS Australia, to his love in 1892. She was a first cousin.

His marriage to Mary Jane Hooper, 24, from Cucklington, a Somerset village three miles south-east of Wincanton, came in 1894. Bailey was 29.

The couple lived initially in the hilltop hamlet. The 1901 census for Cucklington shows Henry J. Bailey, 34, ‘petty officer, navy,’ at home for once with wife Mary Jane, 30, and a trio of pretty little daughters, aged five, four and two.

Ten years later, however, and the family, now blessed with four daughters (a boy having died at only 32 days) is based in Southampton – living on the very same Portswood Road where Bailey had been born.

Aged 45 by that 1911 census, Bailey had left the navy on pension and proudly employed himself as the cox of a steam launch that ferried workers around the docks of Southampton.

So what prompted him to surrender this peaceful and pleasant occupation to suddenly revert to the sea – and his first experience with the merchant service?

The Titanic was Bailey’s first ship of commerce. There is a coincidence, however. His brother-in-law would be aboard the selfsame vessel as a Quartermaster.

Bailey and his wife had been the official witnesses at the 1910 marriage in Southampton of notable Titanic figure Arthur John Bright to Ada Hooper, Mary Jane’s sister.

Ada may have been Bright’s housekeeper by family lore. Certainly there seem to have been some misgivings at the match – Bright, styling himself a ‘widower,’ had been married twice before.

His first wife, Ethel Poulton, whom he married in 1901, divorced him a few years later. On remarriage in 1908 she described herself as ‘the divorced wife of Arthur John Bright’

But that same year, when marrying Emily Jane Harbutt, Bright had also styled himself a ‘widower’ – when such was emphatically not the case.

Wife number two died a year later of heart disease and dropsy, aged 43. Yet there was to be an interval of less than five months before Bright’s nuptials with Ada, below.

The possibly problematic ramifications of Bright’s third marriage – although he and his latest in-laws remained inextricably linked for many years – therefore does not allow the automatic assumption that Bailey applied for a job on the Titanic at Bright’s suggestion.

Bright had been in the Royal Navy at the same time as the new Master-at-Arms of the White Star Line’s premier steamship, and had abundant experience in the merchant service, unlike Bailey.

Their naval careers seemed to parallel each other in the closing years of the previous century, often switching between the same ships, yet hardly intersecting.

They did serve together on board HMS Excellent (The Royal Navy’s gunnery school, a vessel permanently moored at Whale Island, Portsmouth) in October and November 1897, and again from November 1901 to February 1902.

Bright was a petty officer first class at the time, while Bailey was acting chief petty officer, and therefore his senior.

Bright, however, would go on to become known as one of three men who fired Titanic distress rockets that fateful night, giving evidence about it in America, whereas Bailey’s light has remained hidden under a bushel.

Ironically, however, Bailey’s Titanic role was given some prominence in the James Cameron movie of the same name. And it is all the more remarkable that the actor who played the Master-at-Arms, Ron Donachie, should closely resemble Bailey. A case of life imitating art before the fact.

Bailey himself, however, was not necessarily a paragon of virtue in every respect. He had the usual occasional contretemps with authority in the tough milieu of the Royal Navy.

In February 1886, while an AB aboard HMS Canada in the West Indies, Bailey was sentenced to 42 days’ hard labour and sent ashore to serve his time in the military prison in Barbados. His offence? ‘Prevarication’ – presumably quibbling or arguing with an order given by a senior officer.

Then on New Year’s Day, 1892, Bailey spent a few hours in the cells at Portsmouth for the offence of ‘breaking leave,’ which may have had something to do with Auld Lang Syne.

Bailey returned home after the Titanic disaster in poor health, with a respiratory ailment. Every year thereafter he got a cold on his chest in April, which he attributed to his exposure in 1912. ‘After the Titanic he was quite ill,’ declares a descendant.

He may have told his family little, with few details passing down to succeeding generations. One remembered fragment is that they sang on the lifeboat to keep their spirits up, because it was so cold

Bailey was paid £9 7s 6d in expenses to attend the British Titanic Inquiry in London, staying several days, but never receiving the call to give evidence.

This is all the more surprising, given that the Wreck Commissioner, Lord Mersey, had himself raised questions about the Master-at-Arms’ role, asking who had duties aboard akin to those of a policeman, ‘to see that order is kept.’

‘I am told the Master-at-Arms discharges those duties,’ Lord Mersey observed. Yet Bailey was never put before him…

AB John Poingdestre told the Inquiry that ‘no doubt’ third class would be kept back if they made any attempt to gain the boat deck. He suggested (Br. 3209) this would be done by ‘the Master-at-Arms and the stewards.’

‘All barriers were not down,’ he added, squarely.

Poingdestre was saved in boat 12 on the after port side and knew the Master-at-Arms was on duty that evening. Bailey himself was saved in the aftermost port boat, No. 16, while seaman Joseph Scarrott told of having to belay passengers at the intervening boat 14, using a tiller, ‘when some men tried to rush the boats’ (Br. 383)

Scarrott then was joined by Fifth Officer Harold Lowe, who drew his revolver. But no evidence was heard of any trouble at No. 16, despite its still being on the boat deck, representing the closest port-side escape craft for the watching steerage in the stern.

AB Ernest Archer (above) said he went away in No. 16 with ‘another able seaman, two firemen, a steward, and a Master-at-Arms.’ He said in America that Mr Bailey ‘came down after us’ – using one of the ropes in the lifeboat falls, a feat equivalent to the celebrated descent of Major Arthur Peuchen to lifeboat No. 6.

Archer presumed that Bailey had been sent by an officer. ‘He said he was sent down to be the coxswain of the boat. He took charge.’ Bailey, it must be remembered, was an experienced cox who had been operating a steam launch in Southampton.

‘While you were loading the boat was there any effort made… to crowd into the boat?’ asked Senator Jonathan Bourne of Archer, who blithely replied: ‘No, sir; I never saw any,’ adding that there was ‘no confusion at all.’

Steward C. E. Andrews (above) thought lifeboat 16 departed as early as 12.30am, but offers no suggestion that Bailey descended a rope to gain entry. ‘After the boat was full [of women and children] the officer called out for able seamen, or any individuals then, to man the boat.’

Several got in, said Andrews, he himself being the sixth entrant. ‘Five besides myself. The Master-at-Arms - there was two Master-at-Arms, and one was in charge of our boat.’ It is possible, therefore, that Bailey entered at the boat deck.

A relatively early departure of 16 is supported by Quartermaster Robert Hichens, in lifeboat 6, who testified (Br. 1189) that. when they stopped rowing. there was a boat ‘right alongside of us.’ In charge was ‘the Master-at-Arms, Mr Bailey.’

Bailey’s boat was ‘full right up,’ and had ‘left about the same time as we did.’ The two boats tied up together.

Lookout Fred Fleet, also in No. 6, corroborates Hichens –

Fleet: ‘And some other boat came alongside of us, and the Master-at-Arms was

in charge of that boat. We asked could he give us more men.’

Senator Smith: What was the Master-at-Arms’ name?

Fleet: I could not say. He is the only one that survived.

Senator Smith: And you asked him if he could give you more men?

Fleet: Could he give us another man to help pull.

Senator Smith: What did he say?

Fleet: He gave us a fireman

After the ship sank, ‘we heard a lot of crying and screaming,’ said Hichens. ‘The cries I heard lasted about two minutes, and some of them [in Fleet's boat] were saying, “It is one boat aiding the other.” There was another boat aside of me, the boat the Master-at-Arms was in.’

Archer, in boat 16, was asked by Senator Bourne what they did after the ship had sunk. He replied: ‘It was spoken by one of the lady passengers, to go back and see if there was anyone in the water we could pick up. But I never heard any more of it after that.’

Senator Bourne: And the boat was in charge of the Master-at-Arms?

Archer: The Master-at-Arms had charge of the boat.

Senator Bourne: Did this lady request you to go back?

Archer: Yes, sir; she requested us to go back.

Senator Bourne: What did he say?

Archer: ‘I did not hear; I was in the forepart of the boat.’

On his return home, Bailey never again worked on a passenger vessel. He stayed ashore, but willingly returned to service during the Great War, serving his country with distinction for the duration of that conflict.

He returned to the high seas with the Royal Navy aboard HMS Eagle, HMS Victory and HMS Attentive.

After the war, a descendant recalls: ‘I can see him sitting in the chair in the middle room – the breakfast room – downstairs at 659 Portswood Road, and they had Charlie the dog.’

Bailey died on March 12, 1943 at the age of 77. The family Bible records his funeral being held at South Stoneham crematorium, Southampton.

In the same copy of the Good Book, his widow carefully records ‘49 Happy Years,’ a figure that might only have been 18 years - had fate cheated her as it did so many spouses on a numbing night in April 1912.

* Family pictures strictly copyright Bailey descendants. Others courtesy of the author.

© Senan Molony 2010

Comment and discuss